URDL: Defining Baltimore County’s Invisible Wall

By Adam Reuter

If you drive north on York Road past Cockeysville, or west on Reisterstown Road beyond Owings Mills, you notice something happen almost instantly. The dense thicket of strip malls, apartment complexes, and tight suburban subdivisions suddenly vanishes, replaced by rolling hills, horse farms, and forests.

It feels natural, like the city just sort of petered out. It isn’t.

That sudden shift is artificial, intentional, and intensely political. You have just crossed the most powerful, controversial, and invisible boundary in Maryland: The Urban Rural Demarcation Line, known in the halls of Towson as the “URDL” (rhymes with “hurdle”).

For the average Baltimore County resident, the URDL sounds like boring planning jargon. But for developers, community activists, and County Council members, it is the “third rail” of local politics. Touch it, move it, or even whisper about changing it, and you risk political electrocution.

Here is why that imaginary line dictates your commute, your property value, and the future of the county—and why the fights over it are about to get even uglier.

The Billion-Dollar Line

Established in 1967, the URDL was a visionary, if imperfect, attempt to stop sprawl. The concept was simple: draw a ring around the developed core of Baltimore County. Inside the line, the county provides public water and sewer, allowing for density—malls, townhomes, office parks. Outside the line, you are on your own with well water and septic systems, severely limiting how much can be built.

Almost 60 years later, about 90% of the county’s population lives on the “Urban” side, squeezed into one-third of the county’s land mass. The other 10% enjoy the remaining two-thirds of “Rural” land.

Why is it a third rail? Because the URDL is an instant lottery ticket generator.

A fifty-acre farm outside the URDL might be worth a million dollars as agricultural land. If the County Council votes to move that line just a few hundred feet to include that farm, that land is suddenly eligible for public sewer. Overnight, it becomes worth tens of millions to a developer who can now build 300 townhomes on it.

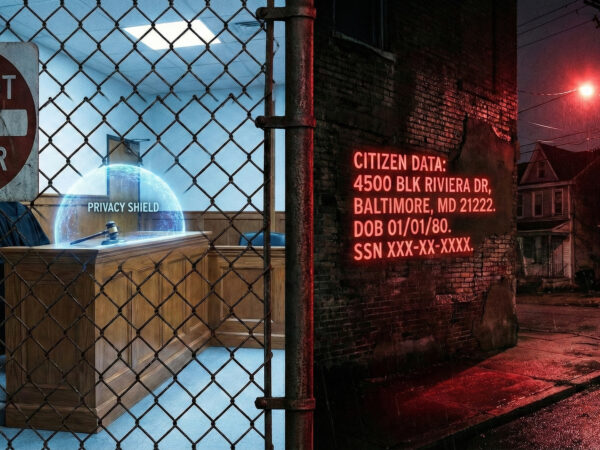

Conversely, for the residents living just inside the line, that boundary is their shield against infinite traffic and school overcrowding. They bought their homes believing the development stopped there.

The tension is obvious. Developers have a massive financial incentive to push the line out. Existing communities have a massive quality-of-life incentive to hold the line firmly in place.

Decades of Trench Warfare

Every four years, Baltimore County undergoes the Comprehensive Zoning Map Process (CZMP). This is when property owners can request zoning changes. It is essentially trench warfare over the URDL.

Over the last two decades, the battles have been intense, expensive, and often shadowy.

We’ve seen protracted wars in the northern valleys—the Worthington and Greenspring Valleys—where wealthy landowners and preservationists have spent fortunes fighting off incursions that would turn horse country into high-density suburbs. The argument there is always about preserving the “character” of the county’s rural legacy against the march of McMansions.

In the eastern and western parts of the county, near White Marsh and Owings Mills, the fights have been different. As those town centers built out, the pressure to expand the “development envelope” just a little bit further past the URDL has been immense. Developers argue that they are providing needed housing stock near existing jobs. Opponents point to roads that are already parking lots at rush hour and schools bursting with temporary trailers.

Every County Executive and Councilmember over the last 25 years has had to walk this political tightrope. They take campaign donations from developers who want the line moved, and they rely on votes from community associations who want the line defended.

When politicians try to please both, you get “spot zoning” or weird exceptions that allow density where it shouldn’t be, leading to the fragmented, traffic-choked development patterns many residents complain about today.

The Pressure Cooker is Whistling

For a long time, the political safe bet was to claim you were “holding the line.” But the dynamics are changing, fast.

Baltimore County is essentially “built out” inside the URDL. There are very few large tracts of easy land left to develop. Yet, we are in a national housing crisis. There is immense pressure from state and federal levels, and from housing advocates, to build more inventory for lower prices.

Where does all that new housing go?

This puts the current administration and County Council in an impossible bind. To build the housing they say we need, they either have to increase density in neighborhoods that already feel overcrowded (political suicide), or they have to move the URDL and open up rural land to bulldozers (also political suicide).

The URDL is no longer just a planning tool; it is the fault line of a class war in Baltimore County. It pits the need for affordable housing against environmental preservation and suburban stability.

The next time you hear the word “URDL” mumbled during a zoning hearing, pay attention. They aren’t talking about bureaucratic lines on a map. They are fighting over the future shape of the county, and who gets rich determining it.